Hardly Existential: Thinking Rationally About Terrorism

John Mueller & Mark G. Stewart

An impressively large number of politicians, opinion makers, scholars, bureaucrats, and ordinary people hold that terrorism -- and al Qaeda in particular -- poses an existential threat to the United States. This alarming characterization, which was commonly employed by members of the George W. Bush administration, has also been used [3] by some Obama advisers, including the counter-terrorism specialist Bruce Riedel. Some officials, such as former U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff, have parsed the concept further, declaring [4] the struggle against terrorism to be a "significant existential" one.

Over the last several decades, academics, policymakers, and regulators worldwide have developed risk-assessment techniques to evaluate hazards to human life, such as pesticide use, pollution, and nuclear power plants. In the process, they have reached a substantial consensus about which risks are acceptable and which are unacceptable. When these techniques are applied to terrorism, it becomes clear that terrorism is far from an existential threat. Instead, it presents an acceptable risk, one so low that spending to further reduce its likelihood or consequences is scarcely justified.

An unacceptable risk is often called de manifestis, meaning of obvious or evident concern -- a risk so high that no "reasonable person" would deem it acceptable. A widely cited de manifestis risk assessment comes from a 1980 United States Supreme Court decision [5] regarding workers' risk from inhaling gasoline vapors. It concluded that an annual fatality risk -- the chance per year that a worker would die of inhalation -- of 1 in 40,000 is unacceptable. This is in line with standard practice in the regulatory world. Typically, risks considered unacceptable are those found likely to kill more than 1 in 10,000 or 1 in 100,000 per year.

At the other end of the spectrum are risks that are considered acceptable, and there is a fair degree of agreement about that area of risk as well. For example, after extensive research and public consultation, the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission decided [6] in 1986 that the fatality risk posed by accidents at nuclear power plants should not exceed 1 in 2 million per year and 1 in 500,000 per year from nuclear power plant operations. The governments of Australia, Japan, and the United Kingdom have come up with similar numbers for assessing hazards. So did a review [7] of 132 U.S. federal government regulatory decisions dealing with public exposure to environmental carcinogens, which found that regulatory action always occurred if the individual annual fatality risk exceeded 1 in 700,000. Impressively, the study found a great deal of consistency among a wide range of federal agencies about what is considered an acceptable level of risk.

There is a general agreement about risk, then, in the established regulatory practices of several developed countries: risks are deemed unacceptable if the annual fatality risk is higher than 1 in 10,000 or perhaps higher than 1 in 100,000 and acceptable if the figure is lower than 1 in 1 million or 1 in 2 million. Between these two ranges is an area in which risk might be considered "tolerable."

These established considerations are designed to provide a viable, if somewhat rough, guideline for public policy. In all cases, measures and regulations intended to reduce risk must satisfy essential cost-benefit considerations. Clearly, hazards that fall in the unacceptable range should command the most attention and resources. Those in the tolerable range may also warrant consideration -- but since they are less urgent, they should be combated with relatively inexpensive measures. Those hazards in the acceptable range are of little, or even negligible, concern, so precautions to reduce their risks even further would scarcely be worth pursuing unless they are remarkably inexpensive.

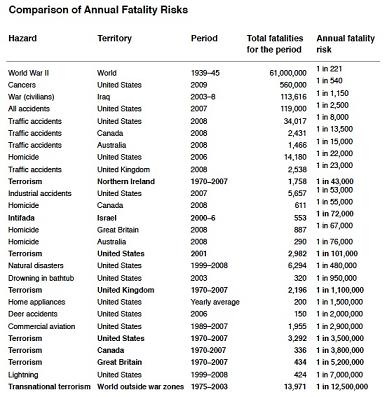

If the U.S. Department of Homeland Security wants to apply a risk-based approach to decision-making, as it frequently claims it does, these risk-acceptance criteria seem to be most appropriate. To this end, the table below lists the annual fatality risks for a wide variety of these dangers, including terrorism.

As can be seen, annual terrorism fatality risks, particularly for areas outside of war zones, are less than one in one million and therefore generally lie within the range regulators deem safe or acceptable, requiring no further regulations, particularly those likely to be expensive. They are similar to the risks of using home appliances (200 deaths per year in the United States) or of commercial aviation (103 deaths per year). Compared with dying at the hands of a terrorist, Americans are twice as likely to perish in a natural disaster and nearly a thousand times more likely to be killed in some type of accident. The same general conclusion holds when the full damage inflicted by terrorists -- not only the loss of life but direct and indirect economic costs -- is aggregated. As a hazard, terrorism, at least outside of war zones, does not inflict enough damage to justify substantially increasing expenditures to deal with it.

Because they are so blatantly intentional, deaths resulting from terrorism do, of course, arouse special emotions. And they often have wide political ramifications, as citizens demand that politicians "do something." Many people therefore consider them more significant and more painful to endure than deaths by other causes. But quite a few dangers, particularly ones concerning pollution and nuclear power plants, also stir considerable political and emotional feelings, and these have been taken into account by regulators when devising their assessments of risk acceptability. Moreover, the table also includes another kind of hazard that arouses strong emotions and is intentional -- homicide -- and its frequency generally registers, unlike terrorism, in the unacceptable category.

In order to deal with the emotional and political aspects of terrorism, a study [8] recently conducted for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security suggested that lives lost to terrorism should be considered twice as valued as those lost to other hazards. That is, $1 billion spent on saving one hundred deaths from terrorism might be considered equivalent to $1 billion spent on saving two hundred deaths from other dangers. But even with that generous (and perhaps morally questionable) bias, or even with still more generous ones, counterterrorism expenditures fail a standard cost-benefit assessment.

Politicians and bureaucrats do, of course, face considerable political pressure to deal with terrorism, but that does not relieve them of their responsibility to expend public funds wisely. If they feel they cannot do so, they should resign or forthrightly admit that they are being irresponsible -- or they should have refused to take the job in the first place. Moreover, although political pressures may force unwise actions and expenditures, they usually do not dictate the precise amount of money spent. The United Kingdom, which seems to face a considerably greater internal threat from terrorism than the United States, nonetheless spends only half as much per capita on homeland security -- at no notable cost to the tenure of its politicians and bureaucrats.

And certainly nothing relieves politicians and bureaucrats of their responsibility to inform the public about the risk that terrorism actually presents. But just about the only official who has ever openly tried to do so is New York's Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who, in 2007, remarked [9] that people have a greater chance of being hit by lightning than being struck by terrorism -- an observation that, as the table suggests, is a bit off the mark but roughly sound. Bloomberg, it might be noted, is still in office.

To border on becoming unacceptable by established risk conventions -- that is, to reach an annual fatality risk of 1 in 100,000 -- the number of fatalities from terrorist attacks in the United States and Canada would have to increase 35-fold; in Great Britain (excluding Northern Ireland), more than 50-fold; and in Australia, more than 70-fold. For the United States, this would mean experiencing attacks on the scale of 9/11 at least once a year, or 18 Oklahoma City bombings every year.

For this to come about, terrorists would probably have to acquire nuclear weapons, the likelihood of which is highly questionable [10]. If that fear is deemed viable, however, the policy implications would be to spend entirely, or almost entirely, on dealing with that limited concern. Massive expenditures to protect "critical infrastructure," for example, are unlikely to be effective against a nuclear explosion.

In fact, there is little evidence that terrorists are becoming any more destructive, particularly in the West. Some analysts [11] have found that, if anything, terrorist activity is diminishing, at least outside of war zones.

As a hazard to human life in the United States, or in virtually any country outside of a war zone, terrorism under present conditions presents a threat that is hardly existential. Applying widely accepted criteria established after much research by regulators and decision-makers, the risks from terrorism are low enough to be deemed acceptable. Overall, vastly more lives could have been saved if counterterrorism funds had instead been spent on combating hazards that present unacceptable risks.

This elemental observation is unlikely to change anything, however. The cumulative increased cost of counterterrorism for the United States alone since 9/11 -- the federal, state, local, and private expenditures as well as the opportunity costs (but not the expenditures on the wars in Iraq or Afghanistan) -- is approaching $1 trillion. However dubious and wasteful, this enterprise has been internalized [12], becoming, in Washington parlance, a "self-licking ice cream cone," and it will likely last as long as terrorism does. Since terrorism, like crime, can never be fully expunged, the United States seems to be in for a long and expensive siege.

Notes:

[1] http://polisci.osu.edu/faculty/jmueller

[2] http://www.newcastle.edu.au/research-centre/cipar/staff/mark-stewart.html

[3] http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/asia/july-dec09/afghanistan3_10-16.html

[4] http://www.nationaljournal.com/pubs/congressdaily/report/tech/march/s080318c.html

[5] http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=CASE&court=US&vol=448&page=607

[6] http://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/reactor-risk.html

[7] http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es00159a001

[8] http://www.bepress.com/jhsem/vol7/iss1/14/

[9] http://wcbstv.com/topstories/Terrorism.New.York.2.244966.html

[10] http://www.icnnd.org/research/Mueller_Terrorism.pdf

[11] http://www.humansecuritybrief.info/index.html

[12] http://www.the-american-interest.com/article.cfm?piece=418

___________________________________________________________________________________

JOHN MUELLER is Professor of Political Science at Ohio State University [1] . MARK G. STEWART is Professor of Civil Engineering and Director of the Centre for Infrastructure Performance and Reliability at the University of Newcastle [2], in Australia. Their book, Terror, Security, and Money: Balancing the Risks, Benefits, and Costs of Homeland Security, will be published in 2011.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Source: http://www.foreignaffairs.com/print/66156 Illustration: http://popolon.org/gblog2/terrorism-is-the-evil-of-the-world-napalm-is-good-for-you