Iran: An Acceleration of Executions

Human Rights Watch

Patrick Mac Manus Blog

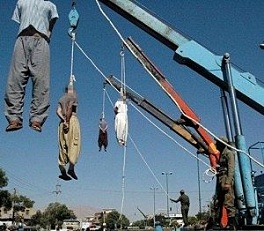

The Iranian government’s high rate of executions and targeting of rights defenders, particularly lawyers, in 2010 and early 2011 highlights a deepening of the human rights crisis that gripped the country following the disputed June 2009 presidential election, Human Rights Watch said in issuing its World Report 2011 Iran chapter. According to Iranian media reports, authorities have executed at least 73 prisoners – an average of almost three prisoners per day – since January 1, 2011.

The 649-page report, the organization’s 21st annual review of human rights practices around the globe, summarizes major human rights issues in more than 90 countries worldwide. In Iran, since November 2009 authorities have executed at least 13 people on the vague charge of moharebeh, or “enmity against God,” following flawed trials in revolutionary courts. The government also harassed, arrested, detained, and convicted several lawyers in 2010 for their work defending the rights of others. At the same time, scores of civil society activists have spoken out against the government crackdown despite facing harsh consequences.

“The noose has tightened, in some cases literally, around the necks of activists in Iran,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “The government’s crackdown has gone beyond silencing post-election demonstrators and is now a broad-based campaign to neutralize Iran’s vibrant civil society and consolidate power.”

The executions and mounting pressures against lawyers took place amid a broad crackdown following the election, and resulted in the killing of dozens of demonstrators by security forces and the detention of thousands of political opposition members and civil society activists. In early 2010 security forces announced that they had arrested more than 6,000 people in the months following the June 12, 2009 election. Those arrested included demonstrators, lawyers, rights defenders, journalists, students, and opposition leaders, some of whom remain in prison without charge. Iran’s revolutionary courts have issued harsh sentences, in some cases based on forced confessions, against dozens convicted of various national security-related crimes.

There were a number of attacks by armed groups against civilians in 2010. Three such attacks during the second half of the year led to the deaths of at least 75 civilians. Iran has used these attacks to justify the execution of anyone convicted of moharebeh, despite evidence indicating that the revolutionary court trials of those charged with this crime did not meet fundamental international fair trial standards, Human Rights Watch said. Iran’s Judiciary operated with little – if any – transparency regarding evidence proving that those sentenced to death were in fact linked to armed attacks.

During the early morning hours of January 24, 2011, Evin prison authorities hanged Jafar Kazemi and Mohammad Ali Haj-Aghai for the crime of moharebeh because of their alleged ties to the banned Mojahedin-e Khalq organization (MEK). Prosecutors had accused the two of sending images of the protests to foreign contacts following the disputed June 2009 presidential election, and shouting anti-government slogans. Prosecutors also used a visit by Kazemi to see his son at an MEK camp in Iraq as proof of his membership in the organization, and alleged that Haj-Aghai had visited the same camp several times. During several interviews with the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, Kazemi’s wife informed the group that interrogators had tortured her husband and kept him in solitary confinement for more than two months after his September 2009 arrest in order to force him to confess to the charges, but that he had refused to do so. Authorities failed to notify the prisoners’ family members or lawyers prior to executing them.

Ali Saremi, a 62-year-old who admittedly sympathized with the ideological and political aspirations of the MEK, was convicted as a member of the group following a flawed trial and hanged in Tehran’s Evin prison on December 28, 2010. During his trial, prosecutors pointed to Saremi’s 2007 speech at a ceremony at Khavaran cemetery in Tehran commemorating the 1988 execution of thousands of prisoners, many of them MEK members, as evidence of his guilt. As in Kazemi’s case, prosecutors used a visit by Saremi in 2007 to a MEK camp in Iraq as proof of his membership in the organization. Saremi denied that he was a member, and the prosecution failed to provide any substantive evidence suggesting that he advocated violence or was involved with the group’s operations, Human Rights Watch said. Like Kazemi and Haj-Aghai, Evin prison authorities executed Saremi without providing the notice to his lawyer or his family members that is required by law.

Saremi was one of a handful of individuals arrested before the disputed June 2009 election on charges of supporting an armed terrorist group who was tried and sentenced to death during the wave of post-election convictions of demonstrators and individuals allegedly involved in what the government refers to as a “coup attempt.” Others convicted after the June 2009 election and currently on death row for allegedly supporting the MEK include Mohsen and Ahmad Daneshpour Moghaddam, and Abdolreza Ghanbari.

In another case, a revolutionary court had sentenced Habibollah Latifi to death for his alleged links with an armed Kurdish opposition group. On December 24 authorities in Sanandaj prison delayed Latifi’s execution, which was to take place two days later, pending further judicial review of his case.

Less than two weeks earlier, authorities had hanged 11 men also convicted of moharebeh for their alleged links to the banned People’s Resistance Movement of Iran, also known as Jondollah. Little is known about the men’s trials and subsequent convictions. The men were executed after a suicide bomber killed at least 39 people in Chabahar in southeastern Iran. The People’s Resistance Movement, which claims to fight for the rights of Sunni Muslims in Iran, had claimed responsibility for the attack. It is not clear whether those executed were arrested after the Chabahar attack or were already in prison.

The 2010-2011 wave of executions of individuals charged with moharebeh due to their alleged involvement in armed groups began on January 28, 2010, when authorities hanged Mohammad-Reza Ali-Zamani and Arash Rahmanipour without providing any notice to their lawyers and family members. As with Saremi, the government had arrested both men prior to the June 2009 presidential election, but tried them as part of the August 2009 mass trials of election protesters, during which they confessed, on state television, to planning a deadly 2008 bombing in the southwest city of Shiraz on behalf of a banned pro-monarchist group.

Nasrin Sotoudeh, Rahmanipour’s lawyer, who is herself now serving a long prison sentence on morality and national security charges, told foreign Persian-language media that authorities allowed her to meet Rahmanipour only once before the trial, for 15 minutes. Sotoudeh, who was ultimately barred from representing her client during his trial, identified numerous other irregularities, including evidence of a forced confession.

On May 9 authorities executed five prisoners, four of them ethnic Kurds charged with having ties to an armed Kurdish group. Authorities failed to notify their lawyers in advance and prevented delivery of the bodies to the families for burial. Human Rights Watch documented numerous trial irregularities in these cases, including viable allegations of torture, forced confessions, and lack of adequate access to a lawyer.

On January 15, 2011, Iranian rights groups reported that authorities had executed Hossein Khezri, one of 16 Kurds then on death row following a revolutionary court conviction for moharebeh. State-controlled media announced that day that prison authorities in West Azerbaijan province had hanged a member of the Party for Free Life of Kurdistan (PJAK), an armed Iranian Kurdish group, but did not reveal the person’s identity. In early 2010 Mohammad Olyaeifard, Khezri’s lawyer, who is currently serving a one-year prison sentence for speaking out against the execution of another of his clients, indicated that although Khezri had admitted to joining PJAK militants in Iraq when he was younger, he had been tortured by his interrogators to confess to taking part in a violent attack on behalf of the armed group despite the fact that he had never participated in the group’s military wing.

There has also been an alarming rise in the frequency of executions for crimes other than moharebeh in recent months. On January 16, 2011, The International Campaign on Human Rights in Iran reported that Iran had hanged at least 47 prisoners, “or an average of about one person every eight hours,” since the beginning of 2011, most on charges of alleged drug possession and trafficking. Citizens of foreign countries are also affected by these executions, including Zahra Bahrami, an Iranian-Dutch dual citizen currently on death row after being convicted on drug charges. The Campaign also reported that between December 20 and January 1, 2011, authorities executed 43 prisoners. These incidents follow several reports by the Campaign in late 2010 indicating that authorities at Vakilabad prison in the northeast city of Mashhad executed hundreds of prisoners, most of them on drug possession and trafficking charges.

In 2009, the last year for which statistics are available, Iran executed at least 388 people and was second only to China in the number of executions, according to Amnesty International. Although figures are not yet available for 2010, human rights groups believe that a sharp rise in the number of reported executions during the second half of the year, particularly of individuals charged with drug offenses, pushes the number of executions for this year well beyond 388.

“Authorities have shown absolutely no regard for human life, whether on the streets of Iranian cities after the disputed June 2009 election or behind the walls of its prisons,” Whitson said. “At the current rate authorities will easily have executed more than 1000 prisoners before 2011 draws to a close.”

In light of the serious concerns regarding the Iranian judiciary’s ability to provide fair trials, especially for individuals charged with crimes carrying the death penalty, Human Rights Watch renewed its call for the Iranian government to issue an immediate moratorium on executions.

The arrests and harassment of lawyers during 2010 appeared to be an effort to intimidate and prevent them from effectively representing political detainees, Human Rights Watch said. Sotoudeh, who has represented numerous people charged with serious national security crimes, was sentenced on January 9, 2011, by Branch 26 of Tehran’s Revolutionary Court, to 11 years in prison and a 20-year ban on practicing law and traveling outside the country. She was convicted of “acting against the national security,” “propaganda against the regime,” and failure to observe the Islamic dress code during a taped message she had sent to the International Committee on Human Rights in 2008. The committee, an Italian nongovernmental organization, had awarded Sotoudeh its Human Rights Prize. Since her arrest in September 2010, prison authorities have held Sotoudeh in solitary confinement for months at a time.

High-level Iranian officials have denied accusations that Sotoudeh was arrested for her activities as a lawyer. Mohammad Javad Larijani, the Head of the Human Rights Council of the Judiciary, recently said that Sotoudeh had engaged “in a very nasty campaign” against the government, referring to several interviews with her by foreign Persian-language media outlets in which she spoke in defense of her clients. On January 20, Sadegh Larijani, the Head of the Judiciary, repeated the government’s warning that lawyers should refrain from giving interviews that damage the government’s reputation.

In mid-January, authorities arrested Reza Khandan, Sotoudeh’s husband, who had provided information to media outlets and rights groups regarding his wife’s condition since her arrest in September.

Officials similarly harassed, summoned, arrested, or sentenced other prominent lawyers and their families in 2010. Mohammad Mostafaei fled Iran after authorities repeatedly summoned him for questioning and instead detained his wife, father-in-law, and brother-in-law when they could not locate him. Mostafaei had represented high-profile defendants such as Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani, the woman sentenced to death by stoning, and numerous juvenile detainees on death row. Another one of Ashtiani’s lawyers, Houtan Kian, is also in prison. In October, a revolutionary court sentenced Mohammad Seifzadeh, a colleague of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi and co-founder of the banned Center for Defenders of Human Rights, to nine years in prison and banned him from practicing law for 10 years.

“Despite the huge personal and professional risks involved, Iran’s lawyers continue to defend the rights of their clients while highlighting the judiciary’s systematic denial of due process rights,” Whitson said. “The international community, especially countries with whom Iran has close relations, should demand that the government stop targeting its rights defenders.”

___________________________________________________________________________________

Source: http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2011/01/26/iran-deepening-crisis-rights?print

URL: http://www.a-w-i-p.com/index.php/2011/01/31/iran-an-acceleration-of-executions