In Afghanistan, Former Guantánamo Prisoners Reflect on Their Ruined Lives

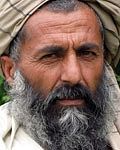

Haji Sahib Rohullah Wakil

On the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, the Washington Post provided a powerful insight into the human cost of Guantánamo, and the problems created in Afghanistan through the intelligence failures that led to innocent people being seized by mistake, and even through the unforeseen knock-on effects of America’s reconstruction efforts.

In Kabul, Staff writer Ernesto Londoño met two former prisoners, Haji Sahib Rohullah Wakil (discussed below) and Haji Shahzada, a village elder in Kandahar province. About 50 years of age, Shahzada, who is a father of six, was seized in a raid on his house in January 2003, with two house guests, and held at Guantánamo for over two years until his release in April 2005.

Shahzada’s story (and that of the men seized with him) was one that had struck me as particularly significant when I was researching my book The Guantánamo Files, as it was a clear demonstration of how easily US forces in Afghanistan were deceived, seizing innocent people after tip-offs from untrustworthy individuals with their own agendas. In Shazada’s case, it has not been confirmed whether the tip-off came from a rival or from members of his family seeking to seize his assets, but the entire mission was a disgrace.

One of the men seized with him, Abdullah Khan, had sold Shahzada a dog, as both men were interested in dog-fighting, but he was regarded by the soldiers involved in the raid (and, subsequently, by US interrogators) as Khairullah Khairkhwa, a senior figure in the Taliban. The problem with this scenario was not only that Khan was not Khairkhwa, but also that Khairkhwa had been in US custody since February 2002 and was held at Guantánamo (where he remains to this day).

In addition, Shahzada, a landowner who had never liked the Taliban, endured numerous aggressive interrogations in which he was obliged to repeat, over and over again, that his friend Khan was not a Taliban commander, and that he had not been supporting the Taliban. He was also particularly eloquent in warning his captors that seizing innocent people like him was a sure way of losing hearts and minds in Afghanistan.

“This is just me you brought but I have six sons left behind in my country,” he said. “I have ten uncles in my area that would be against you. I don’t care about myself. I could die here, but I have 300 male members of my family there in my country. If you want to build Afghanistan you can’t build it this way … I will tell anybody who asks me that this is oppression.”

In his report about Shahzada, nearly six and half years after his release from Guantánamo, Ernesto Londoño noted that he “never leaves home without a neatly folded scrap of paper that is the closest thing to an apology the United States offered after keeping him locked up in Guantánamo Bay for more than two years.”

The document states, “This individual has been determined to pose no threat to the United States Armed Forces or its interests in Afghanistan,” although it also states, as a kind of veiled threat, “This certificate has no bearing on any future misconduct.”

As Londoño noted, however, this is “of little consolation to Shahzada,” as he “struggles to rebuild a life he says is in ruins.” Like other former prisoners who spoke to him, Shahzada said he had concluded that the American presence in his country was “a bigger curse” than the years he spent in Guantánamo.

Around 220 of the 779 men held at Guantánamo were Afghans, although most have been released, and only around 20 remain. As the Washington Post described it, they “serve as legacies of what is arguably the most notorious institution of the US war against terrorism,” and their “different paths reflect some of the unintended consequences of the way the United States has waged this battle.”

Identifying three categories of former prisoners, the Post stated, “Some have again taken up arms against the Americans and their allies. Others have stayed out of the battle but consider their status as a former Guantánamo detainee a badge of honor and express support for the Taliban.” The third group consists of “those who opted to let bygones be bygones, even going as far as keeping an open line of dialogue with Western officials in Afghanistan.”

Shahzada loosely fits into this third category, although he stated that he “remains too angry to forgive.” He added, “I am worried for my life. They destroyed my life, and they made me dishonorable.”

Haji Shahzada

Before his capture, Shahzada, as noted in previous publicly available accounts, “looked after a vineyard in Dand, a village in southern Kandahar province,” which is the birthplace of the Taliban, although that meant nothing to Shahzada. He had fought the Russians in the 198s, but he “sought to keep to himself” when the Taliban rose to prominence in 1994. “They treated people like donkeys, not human beings,” he said.

As the Post noted, “It took several days for news of the worst attack on American soil to reach Shahzada’s dusty village, just south of the provincial capital. It took a few weeks for the first Americans to stream in from neighboring Pakistan hunting for al-Qaeda leaders who had set up shop in this landlocked, impoverished country,” and “It took more than a year and four months for US soldiers to storm into his house,” seizing him on the basis of the thoroughly unreliable evidence outlined above.

In Guantánamo, after the long months of pointless interrogation that he has also spoken about before, he told his Combatant Status Review Tribunal, convened to assess whether the prisoners had been correctly designated on capture as “enemy combatants,” who could continue to be held without rights, “If 20 years from now or even 100 years from now you can find any proof that I helped the Taliban or I was involved with the Taliban, you can cut off my head.”

Although the tribunals were a sham, designed not to honestly assess the prisoners’ stories, but to keep most of them in Guantánamo, Shahzada was one of 38 prisoners judged to be “no longer enemy combatants” at the end of the process, which took place from July 2004 to March 2005, and he was freed in Kabul “with little fanfare,” as the Post described it, on April 9, 2005.

However, on returning home, Shahzada “found his home town transformed.” The “influx of cash the Americans and their allies had poured into southern Afghanistan had had a dramatic effect,” he told Ernesto Londoño, but it had unforeseen consequences that were not beneficial. “I saw reconstruction projects and buildings. That created a lot of disunity among people,” he said. “If one person got money to build a building, his relative would turn against him.”

Shahzada also explained that, around 2007, as the Taliban regrouped in Kandahar, they sought to recruit him. “Since I had been in Guantánamo,” he said, “they told me I should stand alongside them and do harm to the Americans. When I told them I was not ready to join them, they branded me an infidel.” As a result, he said, he had “no option but to abandon his fields, leaving grapes dangling on vines,” and moving to “the relative safety” of the city of Kandahar.

If everything about Shahzada’s story demonstrates the human wreckage of Guantánamo, and the delusional truth about America’s inability to recognize what a disaster it has been, and continues to be, the story of another prisoner interviewed by Ernesto Londoño is more nuanced. With reference to other former prisoners “forced to leave their home towns as fighting has spread around the country in recent years,” he spoke to Haji Sahib Rohullah Wakil, another former prisoner, who has “formed a support group.”

Wakil, who was once a tribal leader in Kunar province, bordering Pakistan, is now living in Kabul as a refugee. “I have a house in Kunar, but I can’t get to it because of the insecurity,” he said, adding that he had “recently met with the US ambassador to Afghanistan and a senior NATO commander to discuss peace prospects.”

He said that many former Guantánamo prisoners had “become pariahs, both in the eyes of the US-led NATO coalition and Afghanistan’s intelligence service, the National Directorate of Security,” and he added that, as a result, some of them had joined the insurgency. Some of them, he might have added, undoubtedly had pressure exerted on them by the Taliban or other insurgents, as happened with Haji Shahzada.

Even so, Wakil, who was released in May 2008, is a contentious figure, and was regarded in Guantánamo as a tribal leader who was opposed to the Taliban but supported al-Qaeda, because of longstanding connections between al-Qaeda and the people of Kunar province. Moreover, in May 2009, when the Pentagon produced a fact sheet, “Former Guantánamo Detainee Terrorism Trends” (PDF), as part of disputed claims that 1 in 7 released prisoners were “reconfirmed or suspected of reengaging in terrorist activities,” he was listed as suspected of associating with terrorist groups.

However, when Nancy Youssef, a reporter for McClatchy newspapers, investigated this claim, seeking out Wakil in Afghanistan, she discovered that he “spen[t] his days going from one high-level official meeting to another” — with President Karzai, his chief of staff, or other presidential candidates — “with the swagger of a tribal elder, advocating for the needs of Kunar province, his home region.” Wakil denied the allegations, of course, but so did others who spoke on his behalf. Presidential candidate Mirwise Yaseeni said, “How could he be a terrorist? He is never far off the government’s radar. His family is here. I have never known him to do anything criminal.”

Youssef explained that “Pentagon officials didn’t respond to a request for comment on why Wakil was included in [the] report that was leaked in May,” although she noted, crucially, that “[t]he discovery that Wakil, far from being in hiding, operates openly among officials of Afghanistan’s US-allied government raises questions about the report’s credibility.”

That was an understatement, as President Karzai’s chief of staff, Omar Daudzai, told McClatchy that Wakil was “an honorable man,” although controversy still dogs him. In August, when a man named Sabar Lal was killed as an insurgent in Afghanistan, it was claimed that he was Sabar Lal Melma, an aide to Wakil who was also held in Guantánamo, and released in September 2007. Wakil and Melma were seized together in August 2002, while attending a meeting with US military officials, but Mohammed Roze, the director of the Afghan government’s Peace and Reconciliation Commission in Kunar, said in 2009 that said that Wakil “was never a threat to American troops,” and, by extension, the same verdict applied to Melma. Roza was convinced that Wakil (and Melma) had been betrayed by the head of a rival tribe, who had persuaded the Americans that he was an enemy.

Although NATO officials said that Sabar Lal “was responsible for attacks and the financing of operations in the Pech District, and was in contact with senior members of Al-Qaeda in eastern Afghanistan and in Pakistan,” and that he was shot dead after coalition forces “located him at a compound near Jalalabad” and he “came out with an assault rifle,” Wakil said that, after his release from Guantánamo, Lelma “chose a civilian life” and “was not in the insurgency.”

Whether or not this is true, Wakil remains an astute commentator on the US presence in Afghanistan. He “said he harbors no ill will toward the Americans who detained him for more than five years,” although he was critical of their “war strategy,” stating that it had “done far more damage than good.” He added that “[t]he Afghan government that the West empowered and bankrolls is hopelessly weak and corrupt,” and that “Afghans continue to be detained without being charged or are prosecuted in an unfair system.” His conclusion was that, “By staying in Afghanistan, NATO soldiers are emboldening the Taliban and allied groups.”

“The existence of the foreign troops is an excuse for the Taliban” to fight, he said. “Once the foreign troops leave, the people will stand against them and defend their districts and provinces.”

Shahzada, according to the Post, had a gloomier prognosis, concluding that “the rifts that the US invasion [has] created in Afghan society will result in an escalation of bloodshed, regardless of how soon the foreigners leave.” He said, “What they have done is created more enmity. Once the Americans go, they will leave behind a river of blood.”

In conclusion, Siyamak Herawi, a spokesman for the Afghan government, said that most former prisoners led “normal lives” after being released. He added that the government estimated that “between eight and 10 percent rejoined armed groups fighting the NATO-backed government.”

That’s an interesting sadistic on which to conclude, as it appears to confirm, once and for all, how the Pentagon’s regularly aired claims of “recidivism” amongst the former prisoners, which involved 74 “confirmed or suspected” recidivists in May 2009, but which rose to 1 in 4 by the start of this year, without any evidence being provided whatsoever, are so unreliable, that they are nothing more than propaganda, pumped out by those with an agenda to keep Guantánamo open, and, presumably, to prolong the occupation of Afghanistan.

1 in 4 of the 600 men released from Guantánamo is 150 prisoners in total, and it is simply inconceivable that this is an accurate figure. In January, the New America Foundation established in a report, “Guantánamo: Who Really ‘Returned to the Battlefield’?” (PDF), that 49 was a more accurate figure for those confirmed or suspected of “engag[ing] with insurgent groups that attack or attempt to attack the United States, US citizens, or US bases abroad.”

That list contained 15 Saudis, 13 Afghans and 21 others, and whereas the Pentagon’s claim would genuinely require the number of Afghan “recidivists” to be around half of those released (around a hundred in total), because there is simply no evidence that released prisoners from other countries (beyond those mentioned in the available reports) are involved in any kind of insurgency, the New America Foundation’s report tallies broadly with the Afghan government’s own figures — between 8 and 10 percent of the 200 or so prisoners released; in other words, between 16 and 20.

I’m not convinced that the New America Foundation report is completely accurate, as I believe some of those cited in did nothing wrong, but as the 9/11 anniversary recedes, and the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo approaches (on January 11, 2012), the accounts in the Post‘s article, and the figures quoted by Siyamak Herawi, ought to contribute to a much-needed understanding that Guantánamo has done incalculable damage to America’s standing in the world, and that, of the 171 men still held, the 89 cleared for release but still held, largely because of Congressional obstruction, and false “recidivism” claims, should be freed as soon as possible.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Andy Worthington is the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK). To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to my RSS feed (and I can also be found on Facebook and Twitter). Also see my definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, updated in January 2010, details about the new documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (co-directed by Polly Nash and Andy Worthington, and launched in October 2009), and, if you appreciate my work, feel free to make a donation.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Published here: Andy Worthington's Blog

URL: http://www.a-w-i-p.com/index.php/2011/09/14/in-afghanistan-former-guantanamo-prisone