Vincent Di Stefano

Thomas Berry wanted to shift the focus of religion to-

Thomas Berry wanted to shift the focus of religion to-

wards care of the Earth.Industrial civilisation has changed everything. At the dawn of the petrochemical age in 1750, atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide were estimated to be 280 parts per million (ppm). In 1960, they were around 360 ppm. Last month (May 2011) levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide were over 394 ppm.

The oceans of the earth are presently becoming more acidic at ten times the rate that preceded the last mass extinction event at the end of the Cenozoic era tens of millions of years ago.

And while Arctic sea ice cover has been steadily declining in recent years, NASA scientists have confirmed that the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are losing mass at a rapidly accelerating rate.

There are many who have read the warning signs. Half a century ago, Rachel Carson alerted us to the damaging consequences of industrial methods of agriculture on ecosystems everywhere. Soon after, Fritz Schumacher urged us to rethink economics in view of the rapacious influence of corporate globalisation. And both Rosalie Bertell and Helen Caldicott have long warned of the silent, slow and spectrous death emanating from the nuclear industry.

The UN Climate Conferences at Copenhagen in 2009 and Mexico City in 2010 were effectively neutered by the influence of mining and energy companies acting through Western governments, notably the US and Canada. Closer to home, both Liberal and Labour parties are desperately outreaching each other in promised tax cuts while arguing about how best to lower carbon emissions by a sad 5% by 2020.

Meanwhile, 250 million tons of coal - over 10 tons for every man, woman and child living in this country - and 10,000 tons of yellow cake - uranium oxide - continue to be shipped out of Australia each year as part of a non-negotiable assault on the earth, felicitously described as a "mining boom", that has replaced the sheep's back on which the Australian economy was once carried.

Those who have understood the magnitude of the environmental situation that presently confronts us are faced with a two-fold task. The first is to clearly identify the nature of those forces that have brought us to where we are. The second is to envision the changes needed - both in our thinking and in our actions - that might reverse the dangerous situation within which we find ourselves, or at the least, prepare future generations for living on the earth in a very different manner.

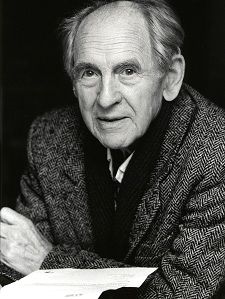

One of the most articulate and visionary allies in this task is the late Thomas Berry, theologian, mystic and cultural historian. Berry combines prophetic clarity with a penetrative erudition grounded in the intellectual and spiritual traditions of both West and East.

His vision was slowly formed through many decades of studying the wisdom traditions and through observing the effects of industrial civilisation on the earth's ecosystems during the twentieth century. Thomas Berry offers a truly heroic vision to counter the pathologies of distraction and trivialisation borne of the post-modern enthralment with transience and distaste for grand narratives.[1][2]